Image

Image

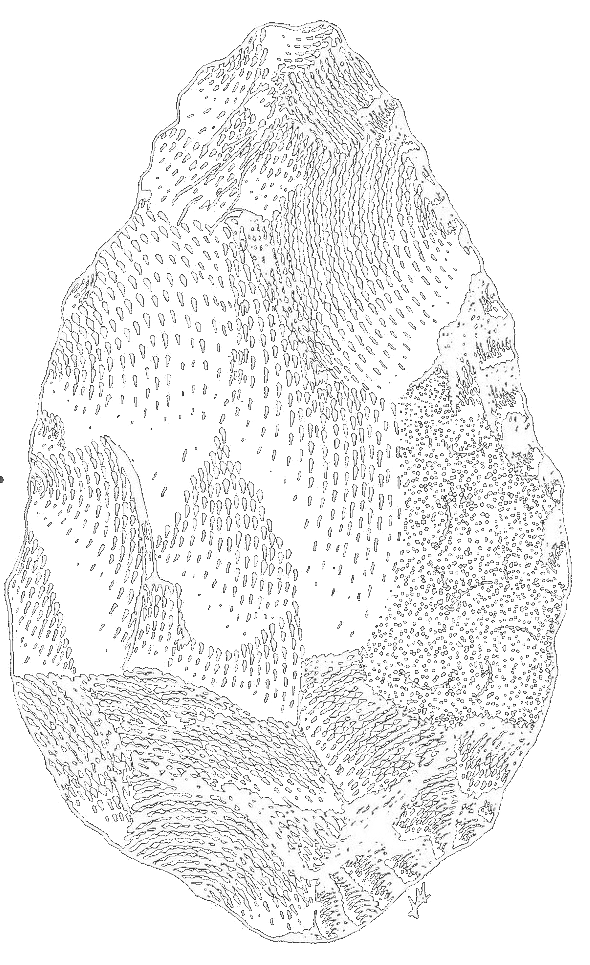

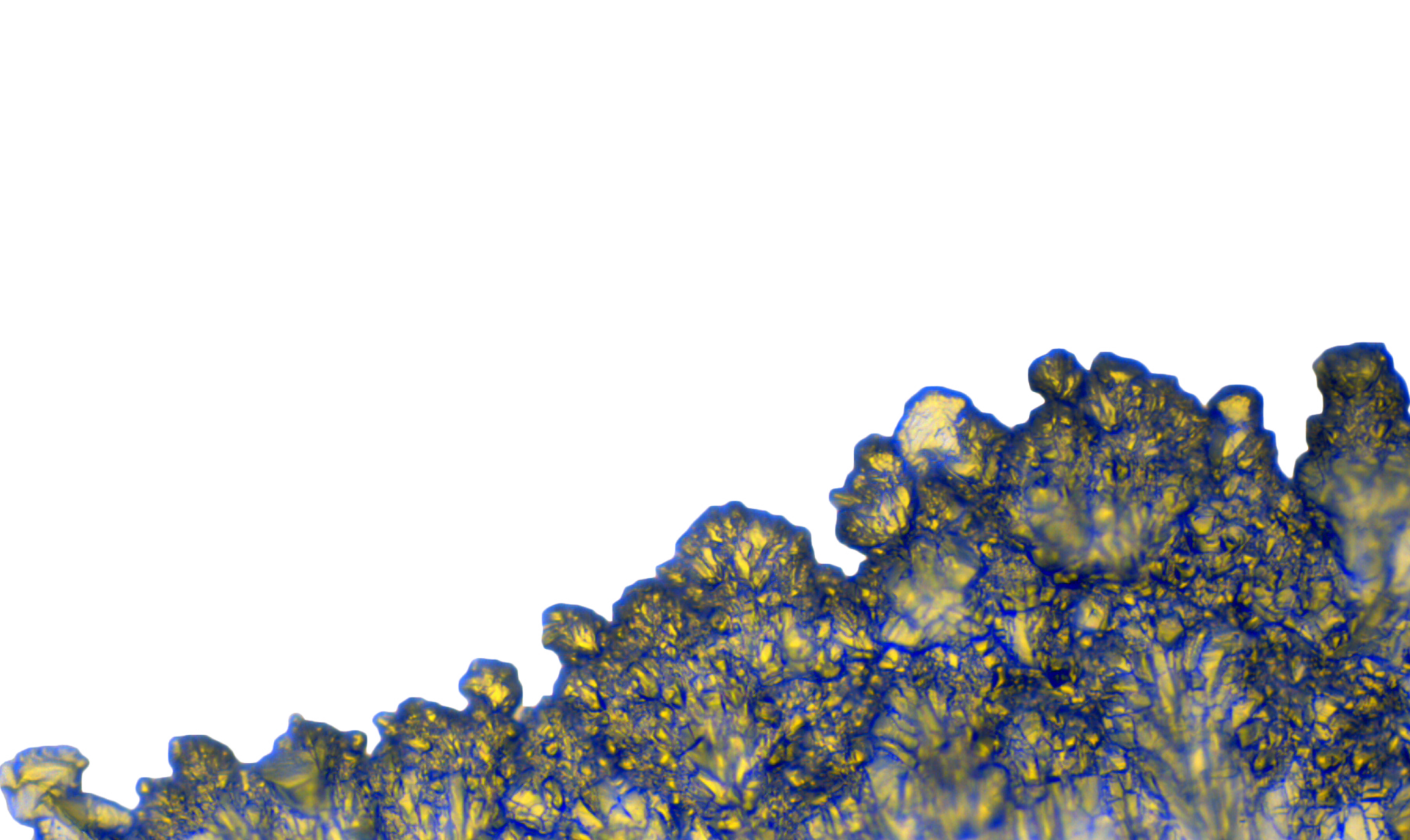

With breakneck pace we have reached a point where the Oriole in the forest excitedly collects plastic fibres for its nest. The average American throws away 65 pounds of clothing per year. Layers upon layers of unwanted objects sedimenting in the Earth’s crust as if it were rock salt or limestone or sulphur. Everywhere we go, everywhere we stand, anywhere we exist, we are surrounded by stuff. I wondered where all of it came from. How did we even begin to invent, create, make, produce, store, collect, curate and hoard all of it. What was one of the first objects we ever made?

The answer for me lay 2.8-million-years in the past, back to when the Hominids in Gona, Ethiopia stood semi-naked and entirely afraid, in front of 13-feet-tall mammoths. Years and years of hunger, fear, desperation, anxiety and duress combusted into a quiet moment of cognisance. A member of the cohort picked up a stone and changed the course of culinary, military, industrial, material and essentially world history.

2.8-million and two years later, we have food and an endless stream of objects, mass produced everyday, imitated and then the imitation mass produced. We consume a million plastic bottles every minute. But now we’re running out of water and the irony is in the fact that the sea levels are rising at the same time. I thought back to the hominids and maybe what’s different for us now is that the giant we stare at today, is the stone itself — the objects around us.

Image

Image

Image

Image

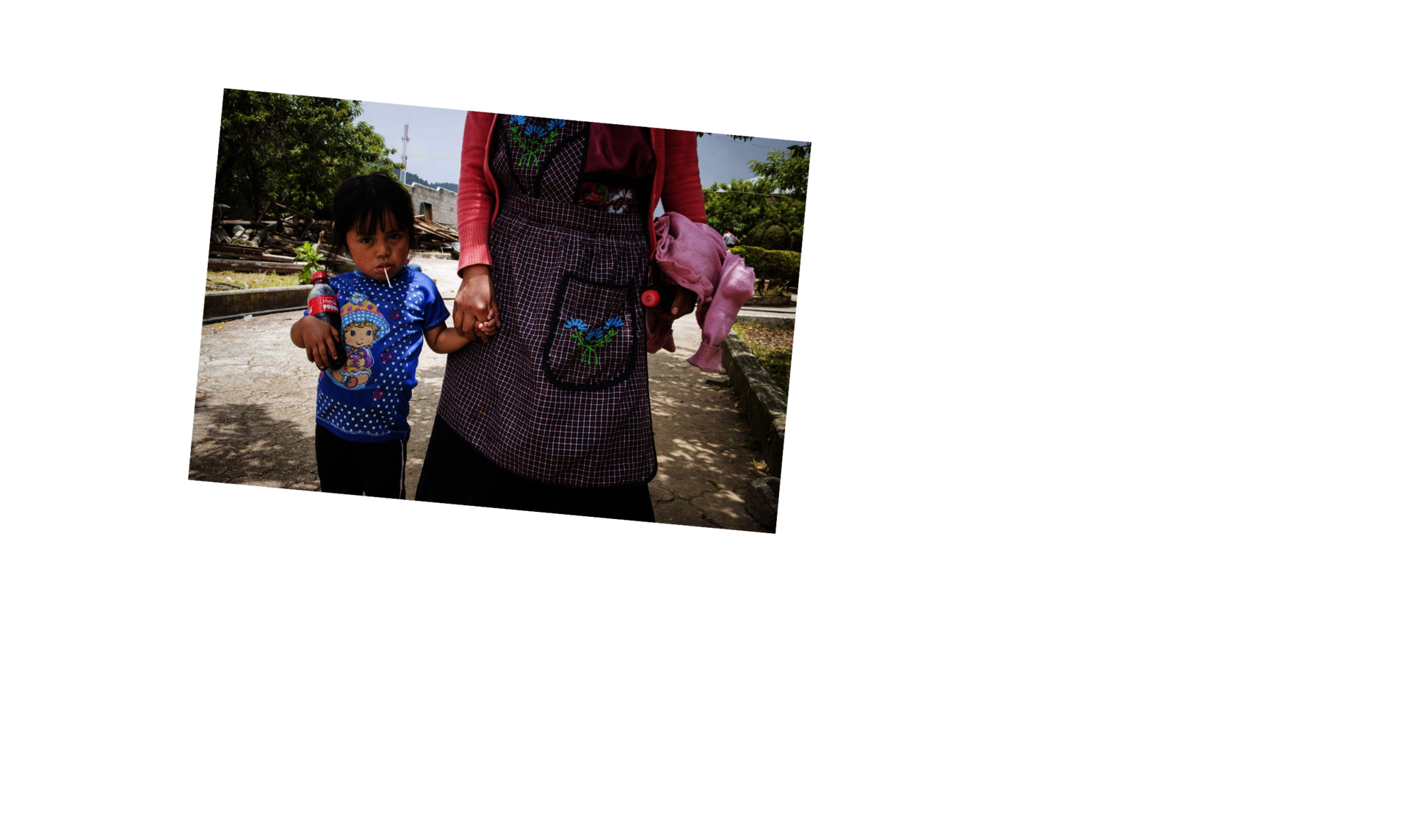

We have lost sight of what our basic need is. 2.8 million years is a long time to sustain a memory. It can be said that our need today is far more fundamental than Maslow’s hierarchy. It’s elemental beyond food, shelter and clothing. Today’s need is clean water and fresh air. Something, as Papanek rightly stated, mankind had taken for granted. Unlike Jugaad, ‘designing under duress’ goes beyond the initial need. It is almost design improv. It requires an adaptable mindset, a level of responsiveness, and an insatiable curiosity — resulting in a design which is idiosyncratic, amounting to its own aesthetic. This system of making is inherent in us. It is our default setting to scavenge for tools — to find and assemble. Our deepest needs are met by this process. Gone is the time of modernism, we are on the verge of ushering in a new future. A future with jugaad and repair at its forefront.

In the grand scheme of things searching for a solution amongst complex realms might be a fallacy. We must look inwards, into our origins. We must look around us. The objects lie dormant like prehistoric stones. We must pick them up, understand them and compose them into tools. Before complexity, we began with something elemental. There was potency within it. At our moment in time in order to progress, once again to the beginning we must return.

Image

Image

Class I

Consists of ‘understanding’, ‘assembling’ and ‘distributing’. The side table falls under Class I. This category is the simplest of the three. Class I is used to make an object which will directly meet the need for which it is being made

Image

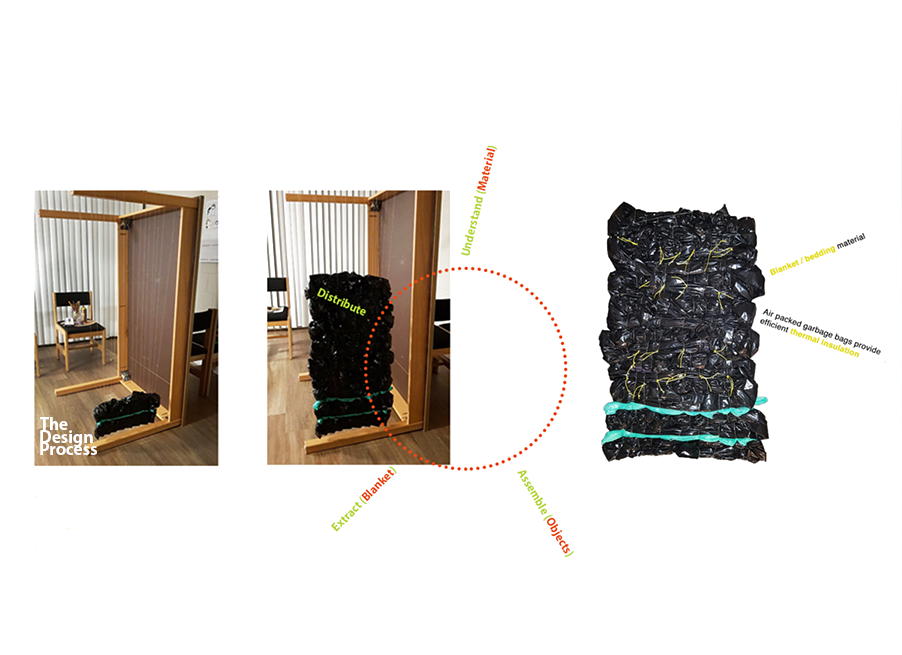

Class II

Consists of ‘understanding’, ‘assembling’, ‘extracting’ and ‘distributing’. This category is used to make an object in order to make the object that would directly meet the need. The example of the plastic bag thermal blanket falls under Class II.

Image

Class III

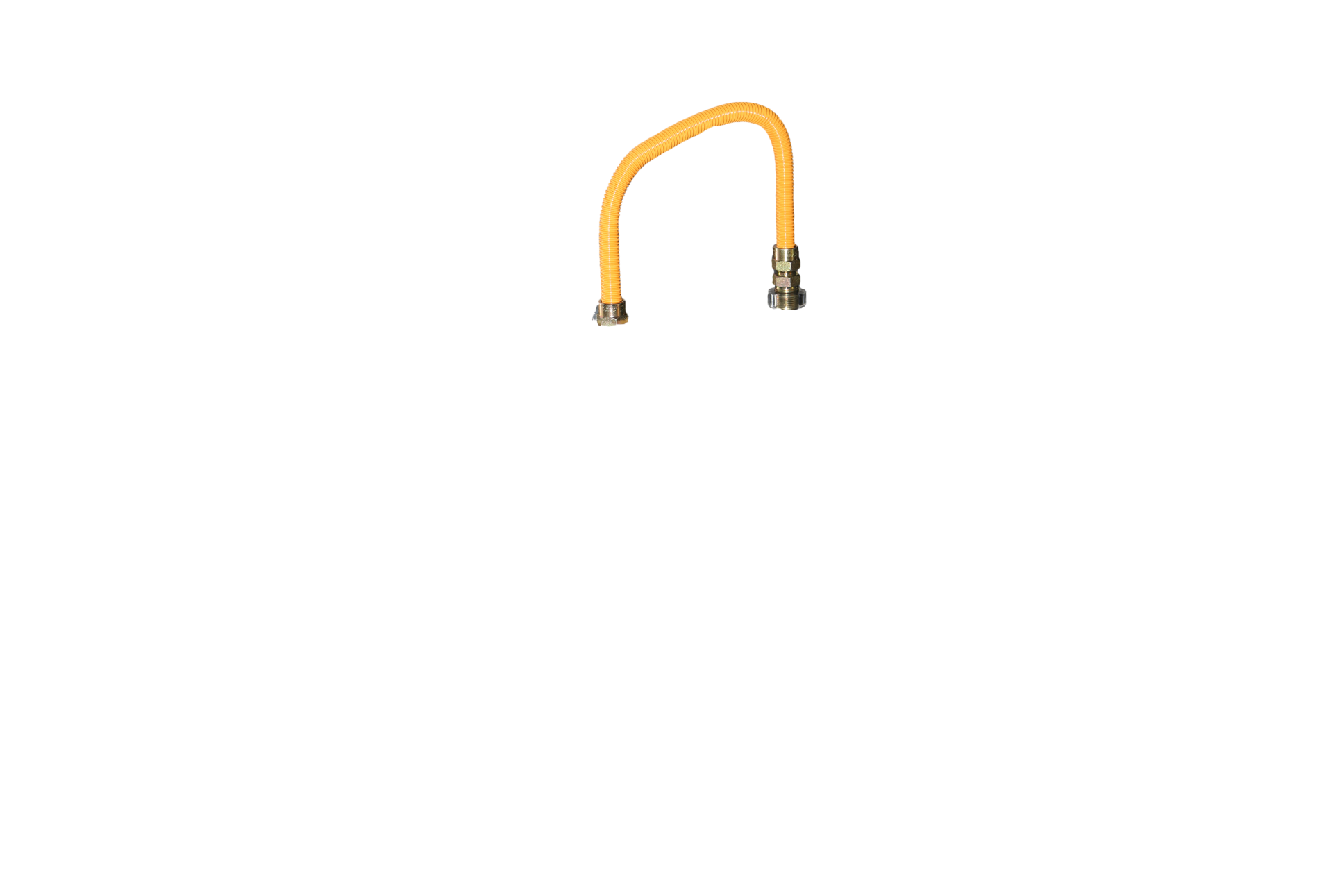

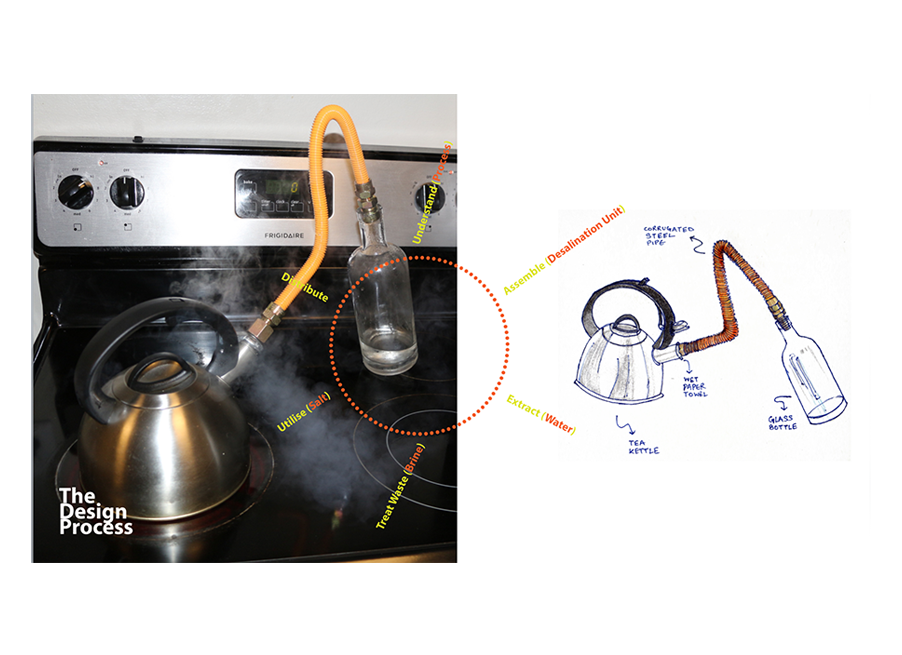

Class III consists of all the six steps — ‘understanding’, ‘assembling’, ‘extracting’, ‘treating waste’, ‘utilising’ and ‘distributing’. This is the most complex of the three categories and represents a lot of the industrial production processes. As a result of the extraction process, we are left with waste. This waste needs to be ‘treated’ and then ‘utilised’ in order to provide an advantage to the user.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

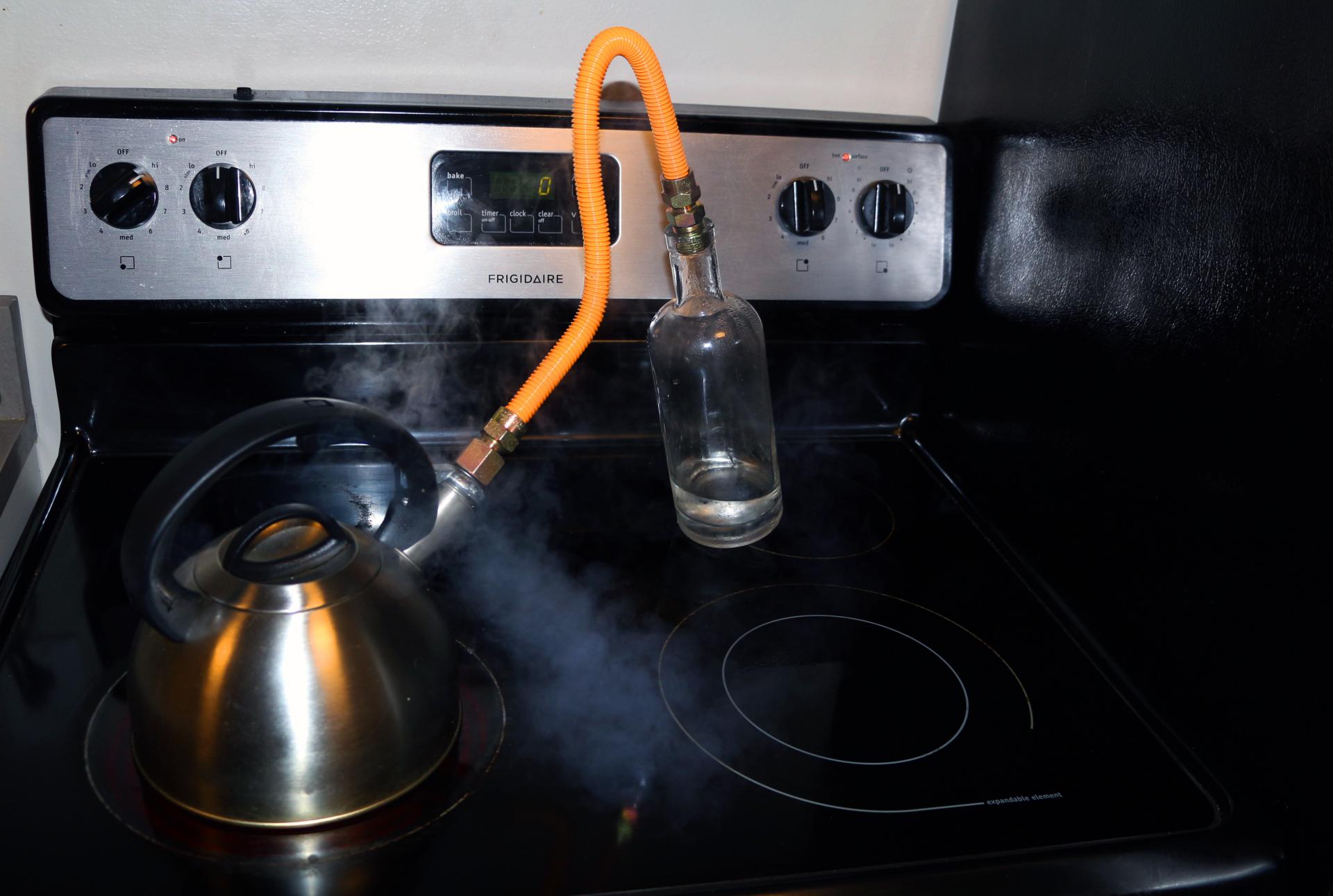

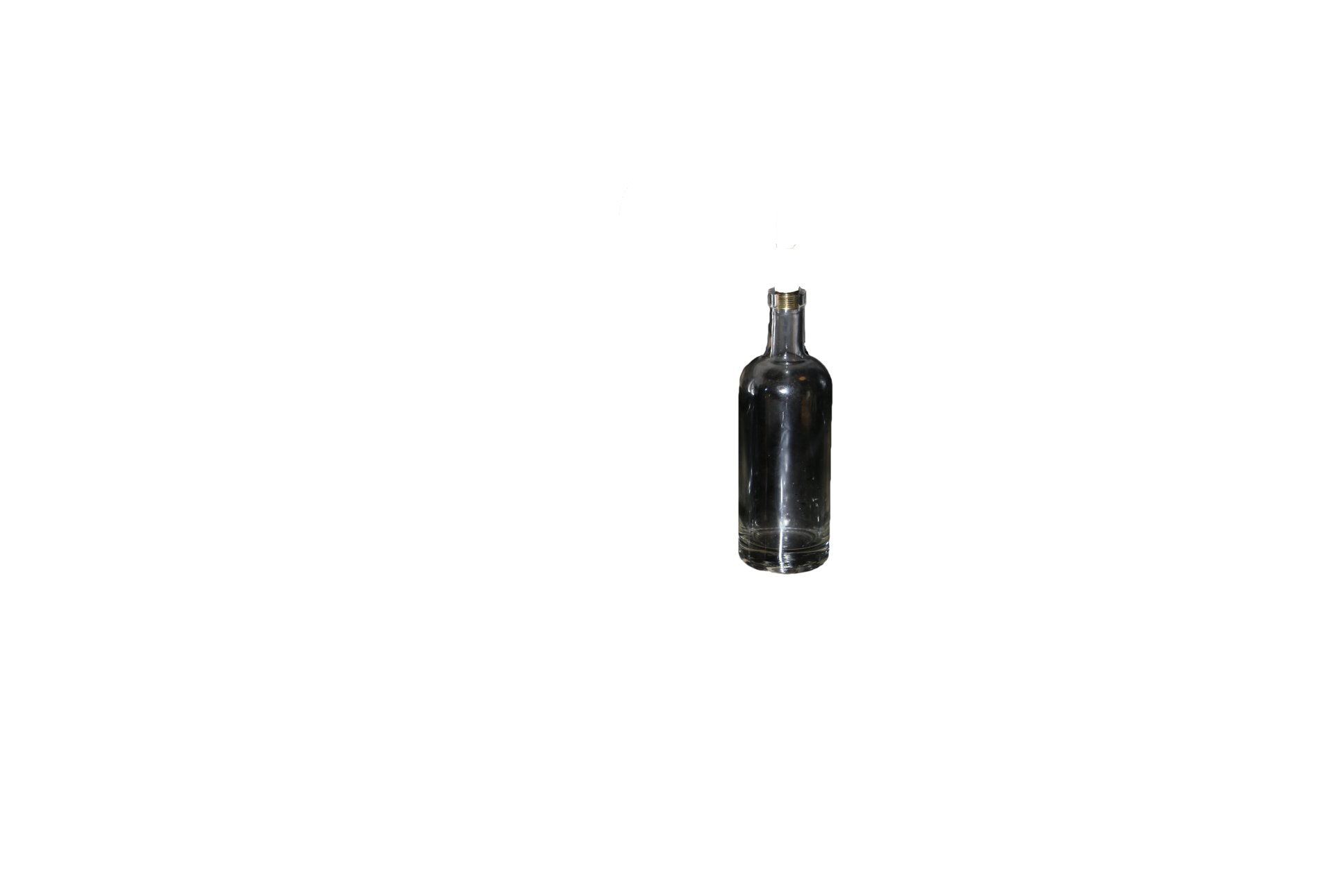

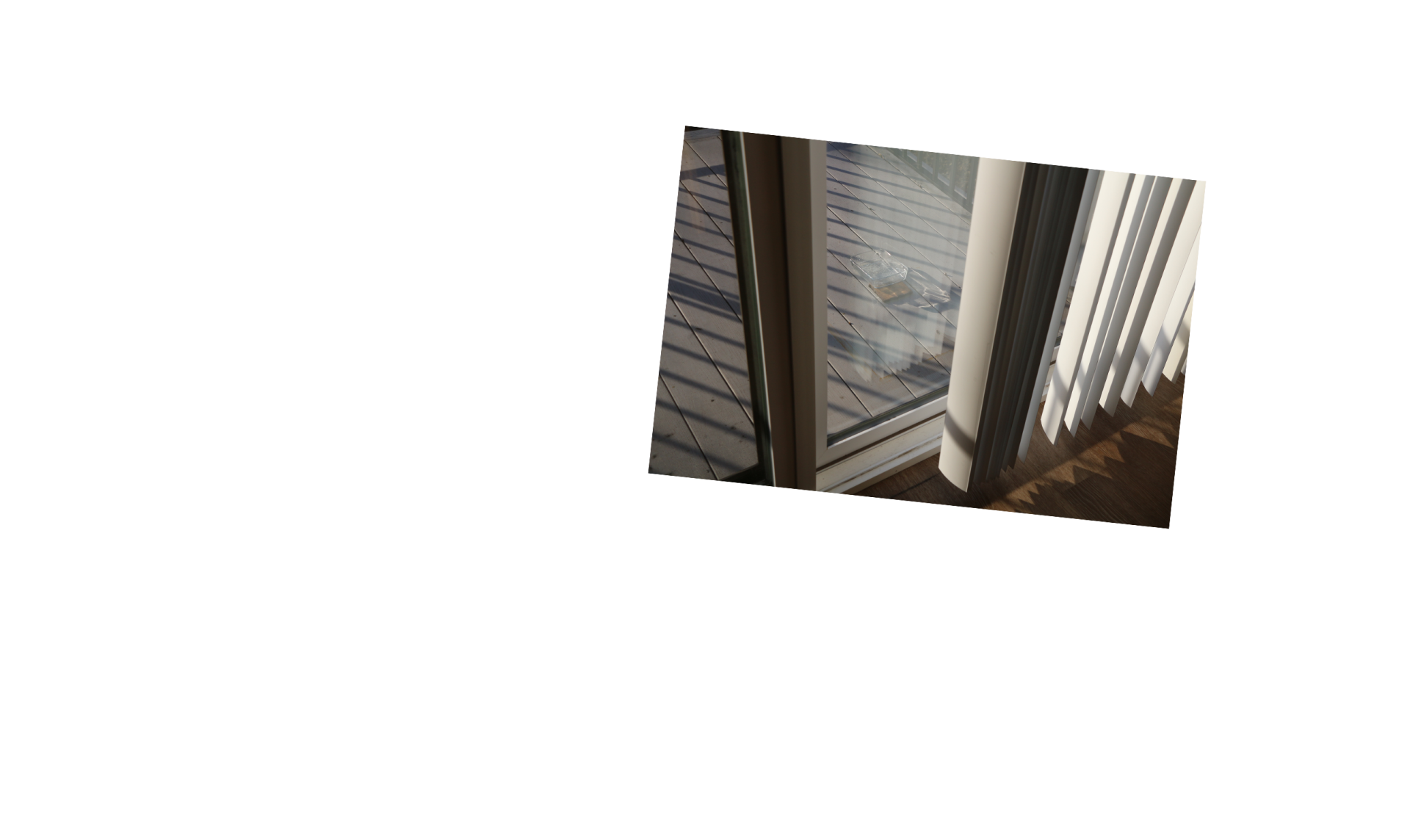

As the kettle came up to a boil, in seconds the bottle fogged up and drops started trickling from the end of the pipe and into the bottle — distilled water. I kept a check on the level of water in the kettle as it concentrated down into a brine. Once the brine is thick enough the bubbling slows down. If the water is evaporated all the way, then the salt would cake at the bottom and start to burn. That’s not the best way to deal with the byproduct. I boiled the brine down as much as I could and then poured it out into a flat rectangular glass food storage container, and kept it out in the sun. In a couple of days, the water had completely evaporated and what was left behind was — beautiful snow white flaky salt.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

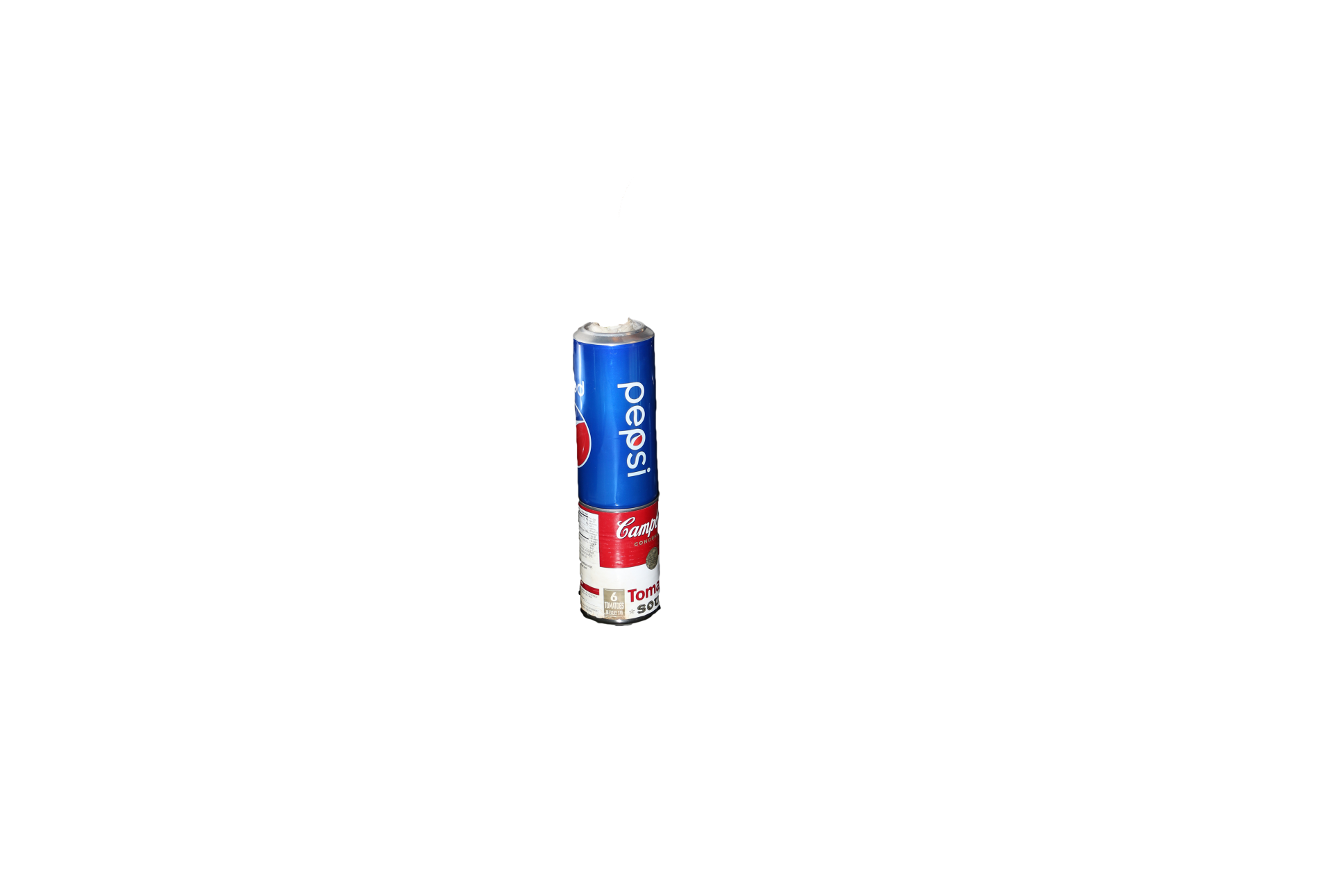

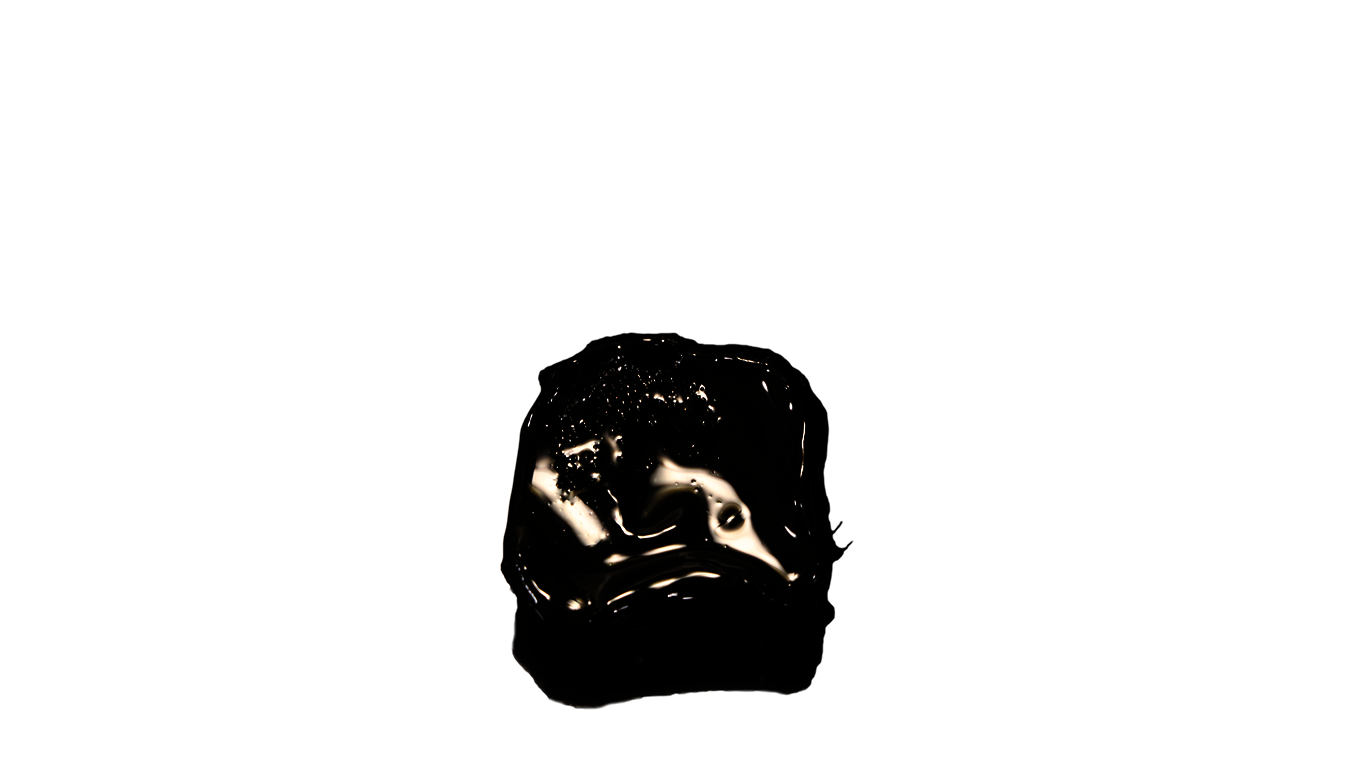

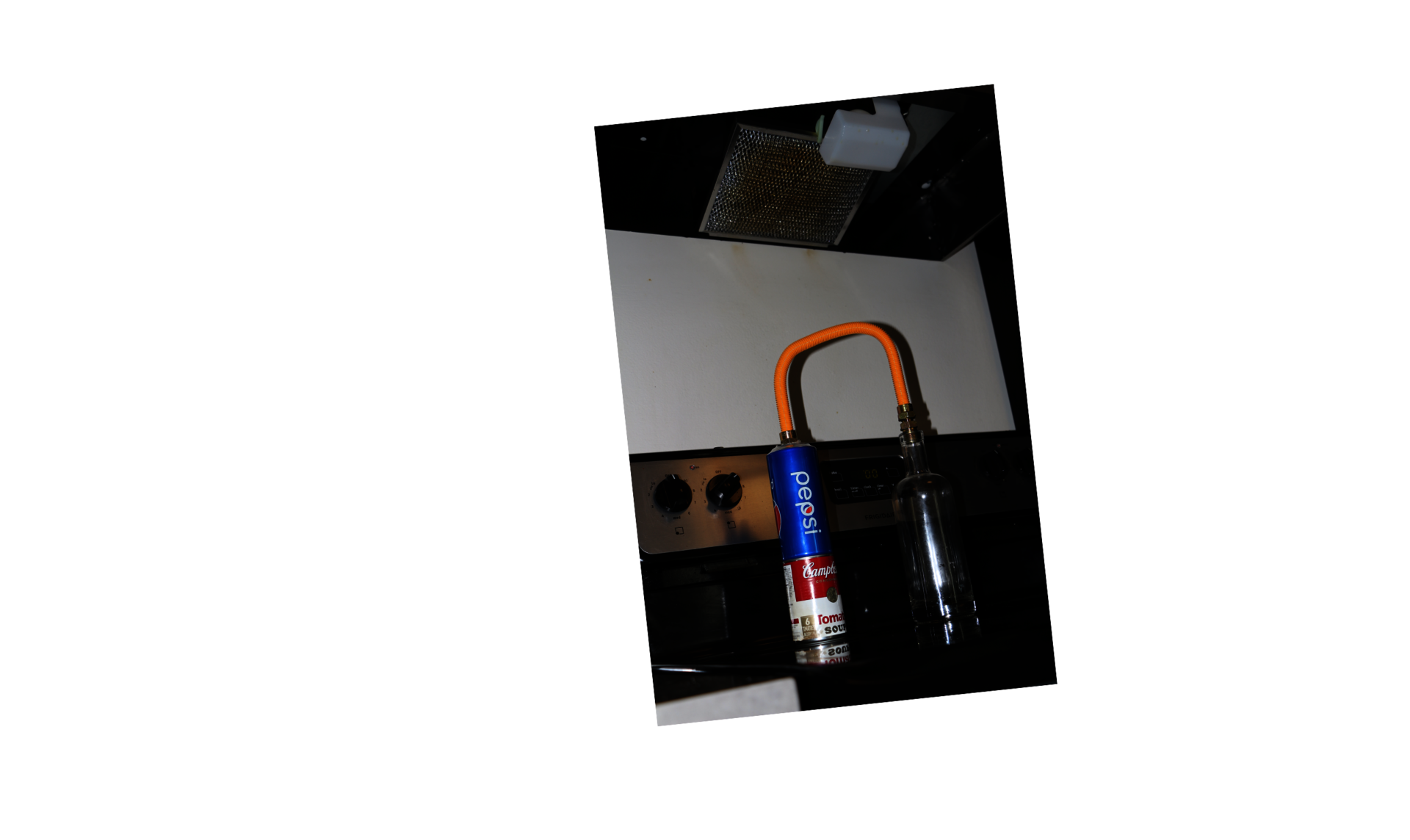

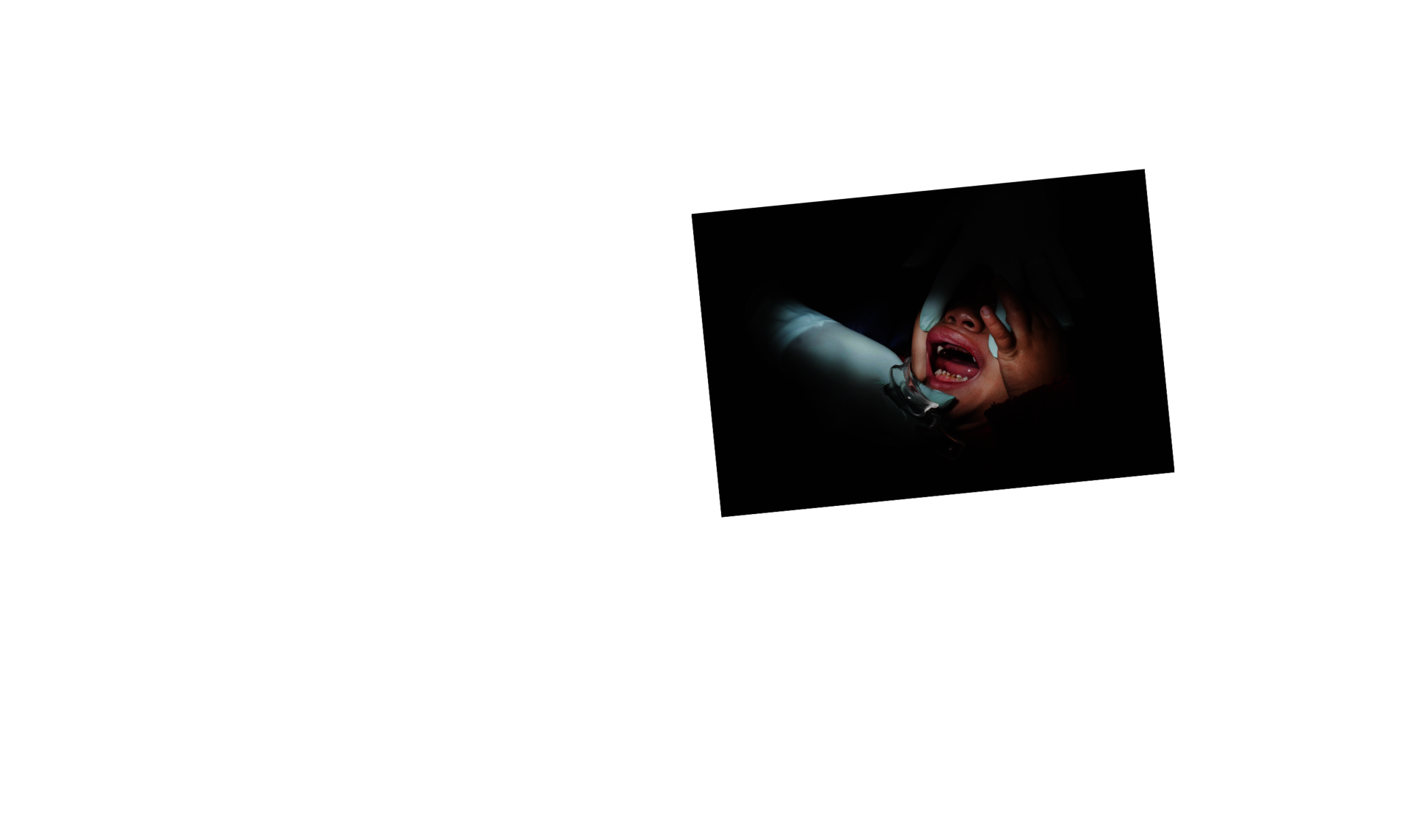

Aluminium’s ability to conduct heat makes it a remarkable heat sink. The idea was to pass the vapour rising out of the soup tin through a heat sink and then through a pipe and into a collection unit. Soda cans are made of aluminium. I cut the end of one and stacked it on top of the soup tin. One end of the corrugated pipe went into the can, while the other end went into the glass bottle. As the Coke boiled — water trickled out of the other end. What remained in the tin resembled satin tar.

Image