Image

S t o r i e s a b o u t r o o t l e s s n e s s.

My most recent work is an attempt to understand the relationship of my art to nature and my sense of rootlessness.

I have been imprinted by the places I have lived in yet disconnected from them as well. I am often situated on the ‘other side’ and as my perspective has learned to shift between the global and the local, between the outsider and insider gaze, I have come to describe this ability as being ‘rootless’. I believe this condition is more common in America, the country of immigrants than anywhere else. Our memories are often re-told in the form of stories as an act of preservation, and a desire to be understood. I have only been able to experience a sense of belonging by being in nature and feeling a connection to its essence or symbolism, its visual characteristics, and natural materials. My work explores how nature is a testament to time and to our identities with their vulnerability and fluidity.

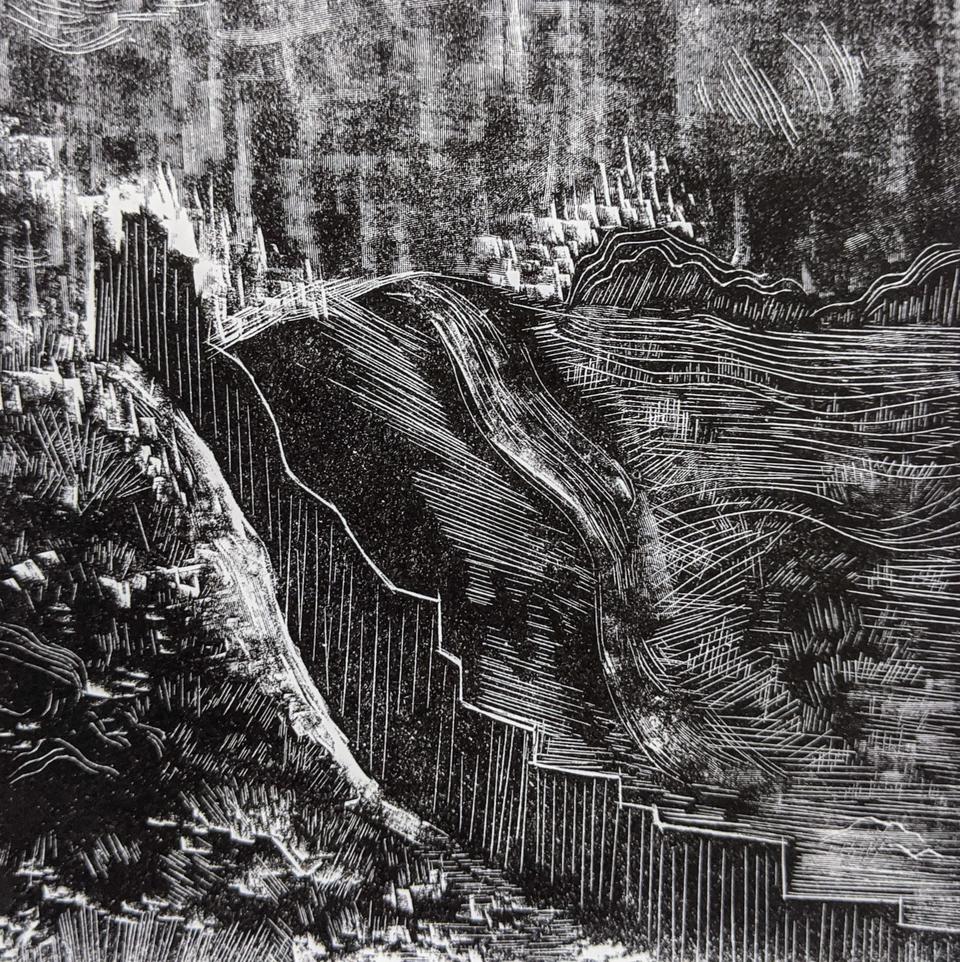

Rootless Aspen, 2020, Intaglio, 13"x13”

Image

The first mention of Transylvania as a place is in a document from 1075, in Latin, and it calls it Ultra Silvam or translated ‘on the other side of the woods.’

Aspen trees are native to the Northern Hemisphere and have been studied for centuries for sharing one (often enormous) root system. Imagine to be such a beautiful, proud and tall specimen covered with majestic white bark! To not only have roots, and deep ones at that, but to have them connect to those all around you. On the other hand, even if you were rootless or independent amongst the system of connected vines, from the ground up you would look exactly the same. You would still be a tree, you would still serve the same purpose. Art has always served as that purpose for me. It is where I can feel connected, even if only from the ground up. The making of things is the other side of the woods.

*

This past winter, it was my privilege to be part of a collaborative group of printmakers learning about wood engraving. We would shed our long winter coats every Monday night and gather around a tiny but warm studio, putting our heads together to leaf through books, discuss, make, and master this old and almost forgotten printing method. Our times spent together have become even more meaningful in light of the school closure and the global pandemic that was to come soon after.

It was during one of these meetings that I came across the book, Growing New Roots: An Essay with Fourteen Wood Engravings by Clare Leighton.

Providence Library visit

Image

Leighton divides immigrants into two different categories, based on the nature of their roots:

"As the roots of some plants stretch wide and flat across the soil, so do the roots of some people. These are moved with relative ease, ... they can find earth enough for their sustenance in the cement of any city ... But there is the other type ... with the long tap roots which seek nourishment deep beneath the surface of the earth .... and as their lives have been shaped by earth rather than by the less individualized world of a city, so do they love it and need it with a poignancy."

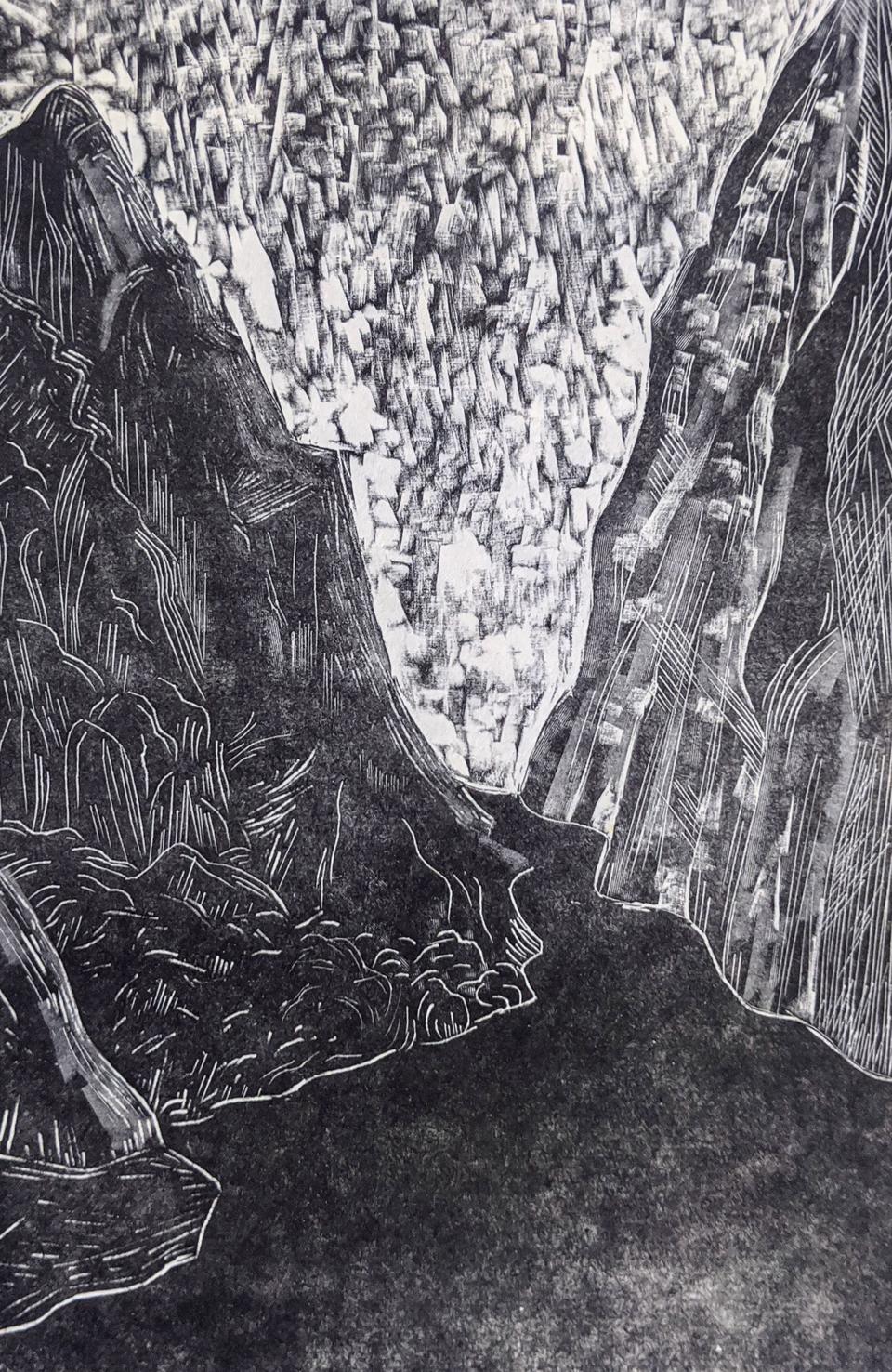

Wood Engravings

*

Torda in Memory, 2019, Photogravure, 5"x3.5”

Image

I have always sought to connect myself to nature, maybe because I do not have one country or culture to connect to. Like ivy clinging to the rough bark of a tree, one can adapt to one’s surroundings. Nature is full of contrasting features–fragile or strong, temporal or enduring, accidental or purposeful, native or invasive. Some materials are both–like the fibers or paper which are so small and soft yet together with water that can form a strong woven bond.

Material and place are interchangeable in my process and they constitute an index, or trace of time and place That is one of the reasons why I found the print to be such a fitting medium. The gradual process of making a print is like the process by which we build our memories. As we experience things, our brain collects key elements and stores them. When we try to remember we rebuild the particular experience and add on our 'baggage' such as feelings, myths, facts, or even beliefs.

...I often wonder how my memories of these landscapes of my lands compare to the reality of them. Would they even recognize me?

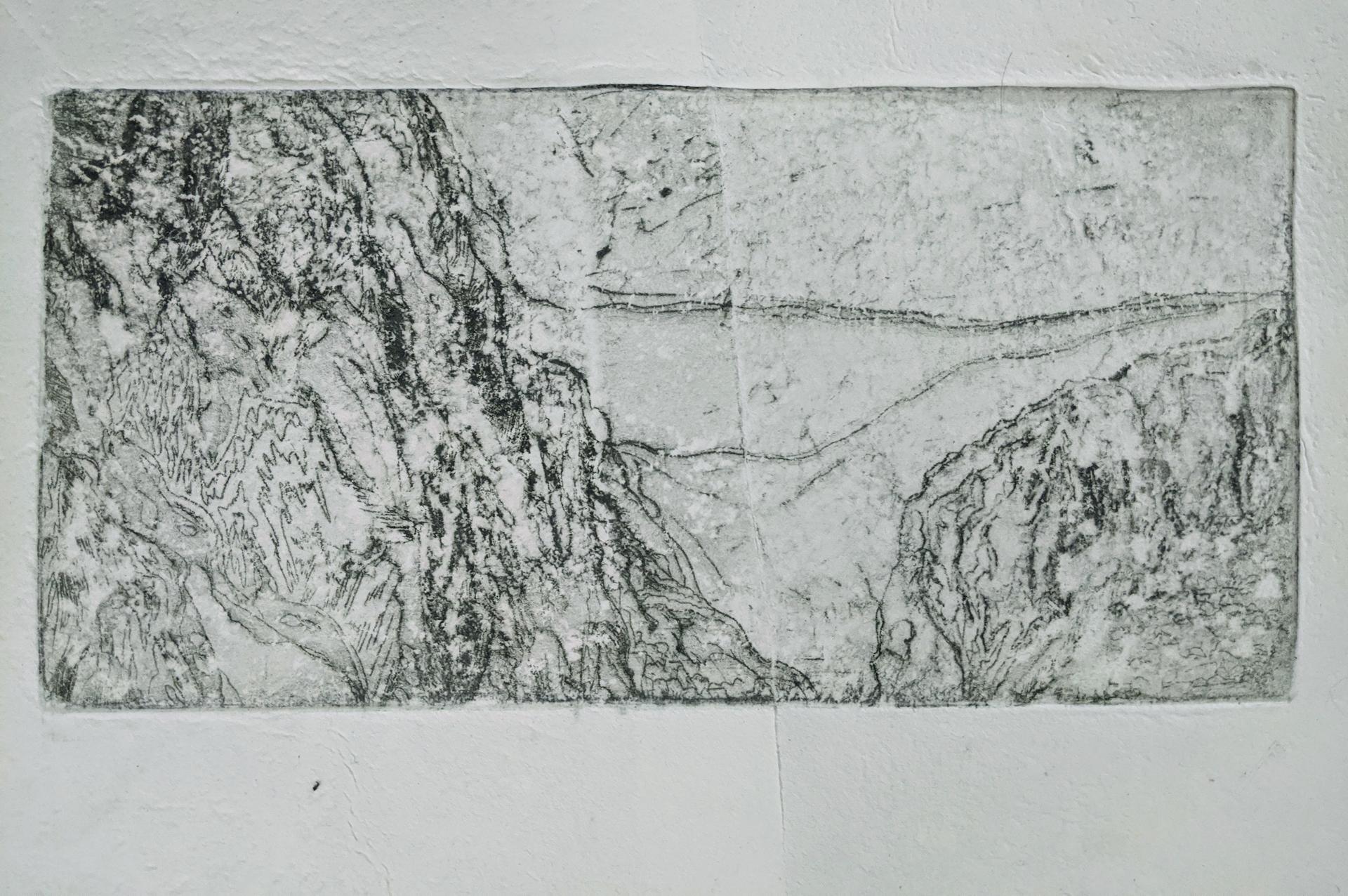

On the other Side, 2019, Monotype, Relief, 11"x8”

Image

The idea of home is like a mirage to the immigrant. Something to strive towards, never within reach, and more of an illusion than a place. Home is your memories which belong only to you.

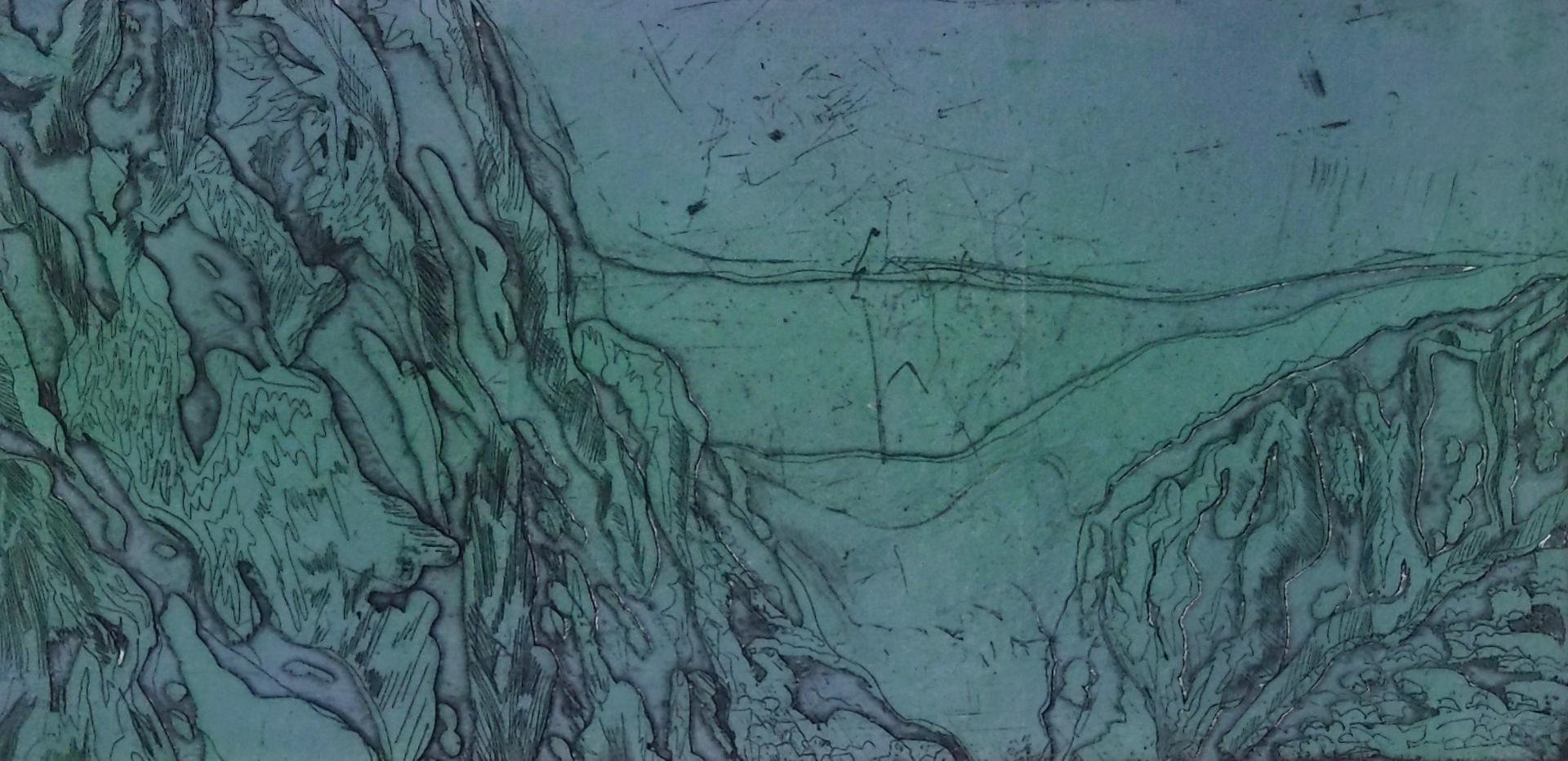

Blue Mountains, 2020, Intaglio, 4"x7”

Image

I read a story once of a young doe in a forest who was afraid of the dark shadows and dangers around her. From the large meadow, where the deer went to eat you could see far far away, over wide mountains, large valleys, dipping hills to distant mountains. These mountains were blue, pure, innocent blue. And the young fawns, who were still learning, would ask their mothers why are these faraway mountains blue? The mothers would always answer because over there exists no beast (human or animal), only peace. It is always warm, never snow or frost or wind. Then the little ones asked why they could not all go there, only to hear the same answer accompanied by a great sigh each time: it is not possible. ‘How do you know what they are like then?’ they would ask. ‘Because our elders told us they came from there’ the mothers would say.

But then one day, one of the fawns decided to find her way to these blue mountains. She followed the original trail, even as the landscape became more rugged and the climate got colder and colder. Finally, she met a buck and he whispered: “Run! The wolves are coming!” For a while, they ran together until the buck asked the doe where she was from. “From far far away,” panted the doe all out of breath while pointing backward with her snout. “From the blue mountains,” asked the buck, his mouth open in surprise. The doe looked back stunned, only to see blue mountains in the distance, the mountains of her home. All a sudden she felt a desire for that old meadow, for the sparkling springs, and young pine trees. “That can’t be”–answered the buck–"our elders told us that it is a place with no beasts, humans or animals. Just peace and warmth, never cold or danger.” But the doe nodded, yes with a heavy heart and turned around. Without looking back, her head down, she started towards the blue mountains. By the time she neared the edge of her forest, it was snowing.

One of the young fawns saw her and ran up to her excited to inquire: “Did you find them? The blue mountains? You came back for us, to take us with you for it is bad here, cold and dangerous.” The doe stopped and looked back at the mountains she journeyed to, shaking her head slowly. “Our mothers are right, you can’t go there.” she said quietly. *

*Based on the story MESE A KEK HEGYEKROL by Albert Wass

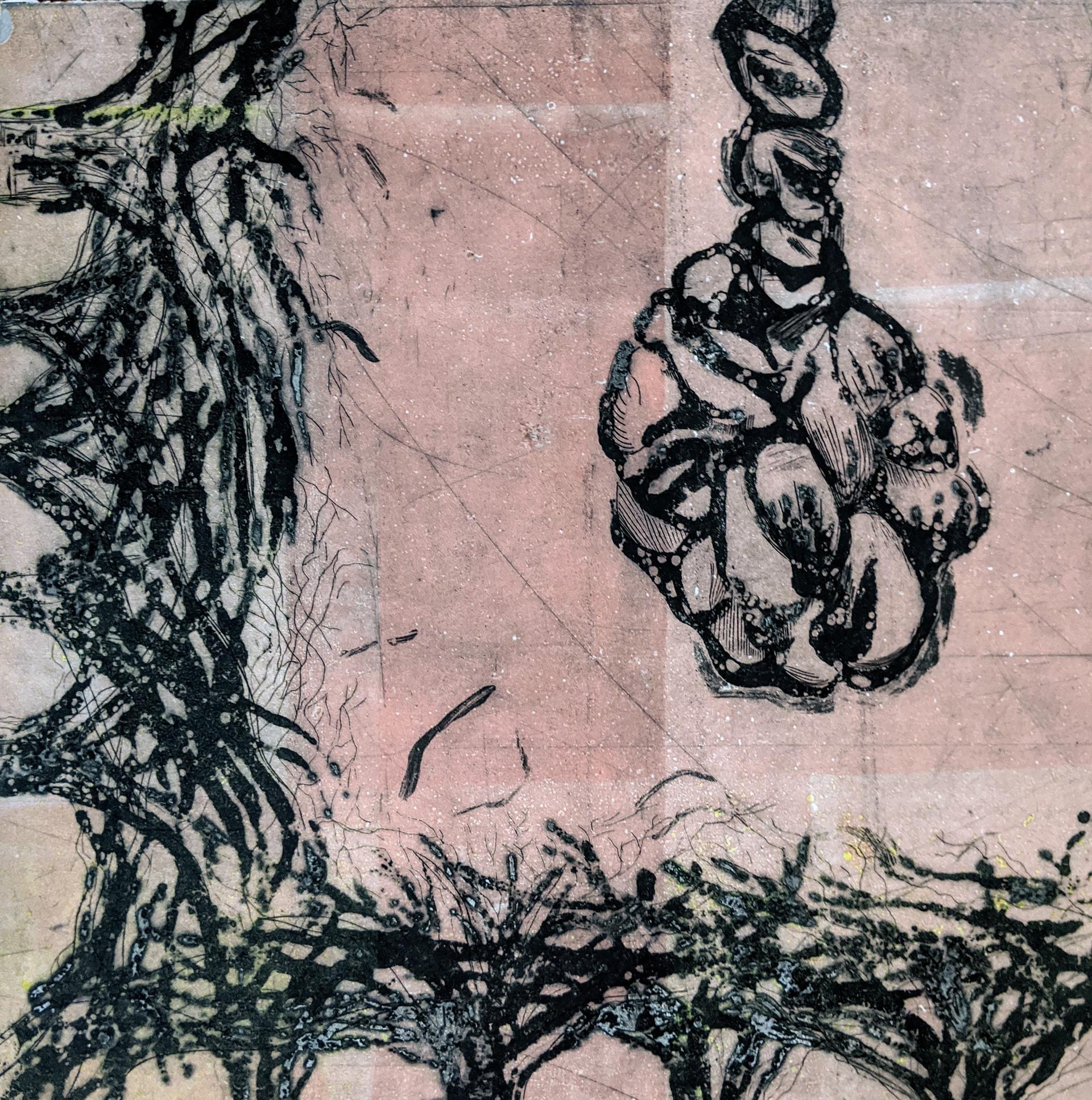

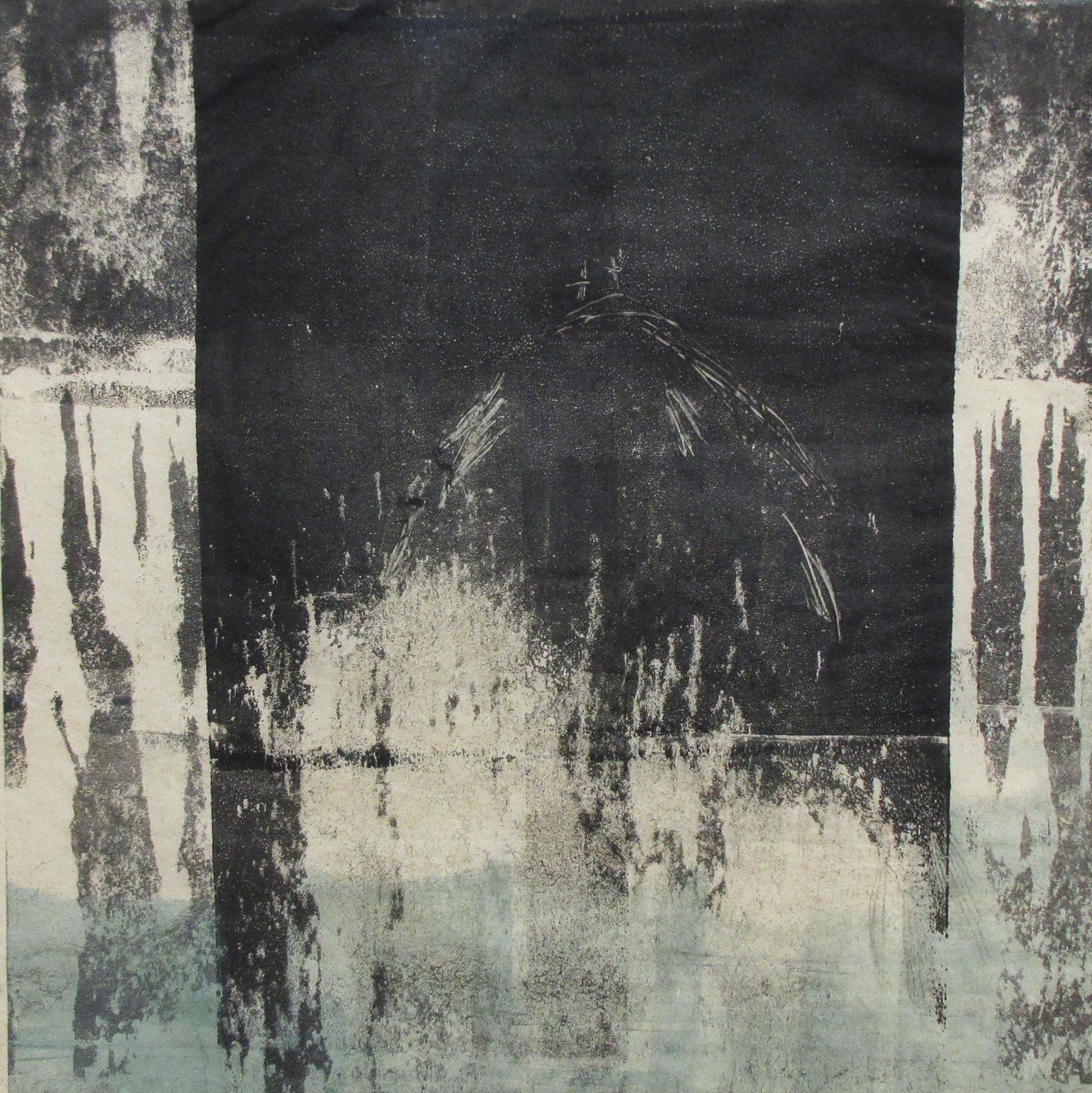

Oltarko, 2019, Monotype, 12"x12”

Image

The hyper-awareness of the vulnerability of nature, of its changing and unchanging qualities, often lends itself as the starting point to my work. A specific moment remembered is my matrix, or point of departure, but it is in no way the end. Printmaking allows me to impose some guidelines and use exploratory techniques to search for a conclusion in a sequential manner even when there might not be one. I try to honor nature as a testament to the time and belonging.

I do not make art to describe nature. For such an endeavor feels so futile. I do not even make art to describe places. For how could I possibly do them justice? Even if I were in the middle of the landscape every time I made a mark, I could still not trust my depiction of it. For by the time this blundering attempt made it home, the leaves might have changed color, the birds might have flown the nest, the stream might have dried up, the trees might have been cut down, the factory might have been built. No, I make art to open the door, to bridge the gap, to connect the shards, to contemplate, to commemorate, to praise, and to be free.

*